Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice: Whatever Happened To Vocational Education?

Where and When Did Vocational Education Begin?

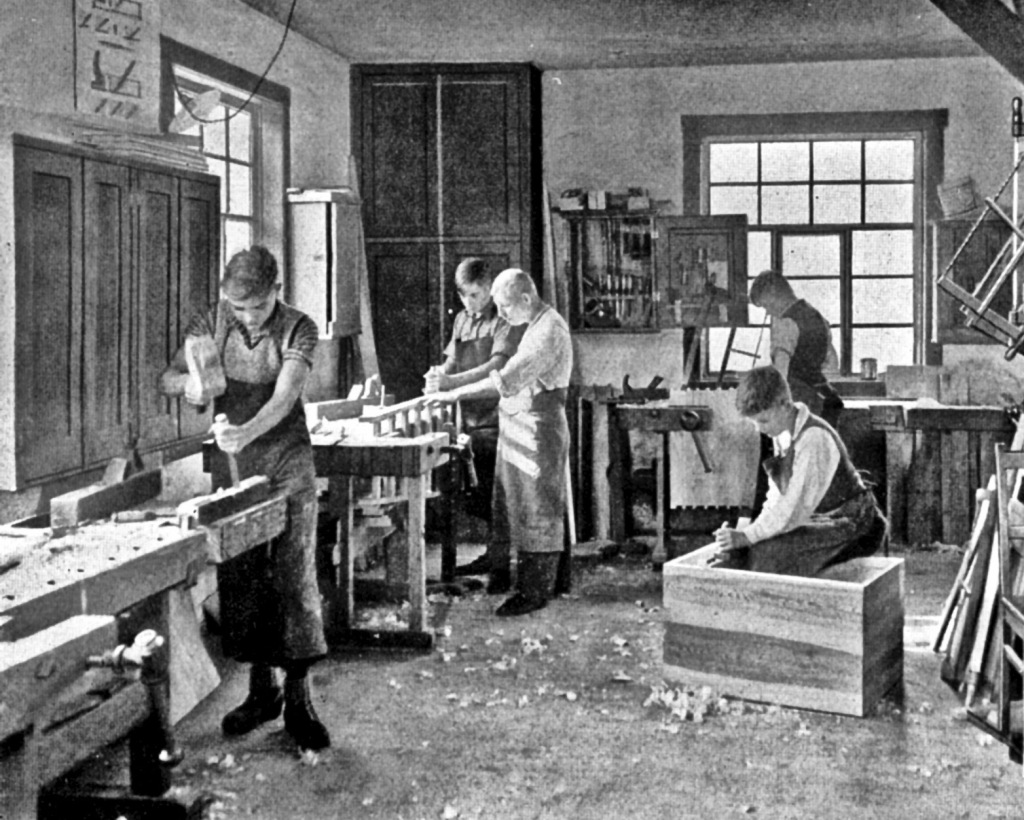

In the mid-19th century, school reformers made the distinction between the head and hand learning in children and youth–both had to be schooled. After the Civil War, reformers introduced “manual education” into schools. Working with tools to fashion wood, iron, and other metals into useful objects, balanced the nearly total focus on academic subjects (see here and here). While adding such courses to the high school curriculum was common in the closing decades of the 19th century, separate manual training high schools in cities were also built such as the duPont Manual High School in Louisville (KY), Manual High School in Denver (CO), and Armstrong Manual Training School in Washington, D.C.

But the economy that welcomed artisans in carpentry, brick masonry, and farriers was shifting to industrial workplaces where different skills and different gatekeepers to jobs were needed.

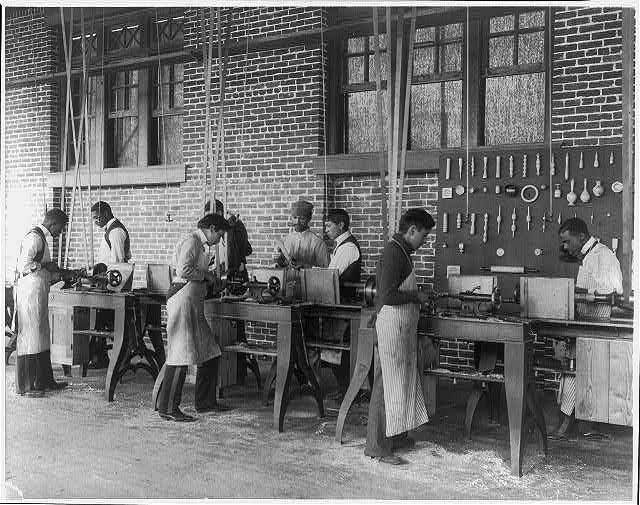

In the early decades of the 20th century, business and civic leaders called for a different kind of “hand” schooling to prepare youth for newly created industrial and manufacturing jobs as machinists, iron and steel workers, etc. Many of these leaders had visited Germany, a global competitor now outstripping the U.S. in selling its products. They saw how Germany had established vocational education and apprenticeships in secondary schools and how these schools provided a ready supply of workers fitted to a rapidly changing industrial economy. By World War I, U.S. high schools had added “vocational” subjects to the academic curriculum and districts opened newly established, separate vocational schools.

What Problems Did Vocational Education Intend To Solve?

incorporating vocational education into the high school curriculum sought to solve two problems. First, the wholly academic curriculum of the 19th and early 20th century high school drove most students to dropping out of school while in grammar school (grades 1-8) or immediately after graduating. Adding work-related courses that could equip students with workplace skills and lead to actual jobs enticed students to continue going to school. In a democracy, Progressive reformers wanted the high school to educate all students, not just to those who prepared for college.

Second, public high schools with their concentration on academic subjects were largely divorced from the economy. As the nation became an industrial democracy, Progressive reformers pressed for a better fit between schools and the economy. In 1917, the Smith-Hughes Act had the federal government for the first time funding local schools that introduced vocational subjects into the curriculum for both boys and girls. Since then the federal government and states have repeatedly legislated vocational education as a key part of work training in U.S. high schools. Thus, Progressive educators were victorious in adding the goal of vocational preparation by the 1920s (see here and here).

Third, racial discrimination dominated the ways of bringing Blacks into industrial and skilled jobs within a highly segregated society that dictated what Blacks and whites could do for a living (e.g., trade unions banned Blacks from entering apprenticeships and journeyman postions through mid-20th century).

In the decades following the Civil War, vocational education in the Black community had a model to follow in the work of Samuel Armstrong at the Hampton Institute in Virginia and Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The vast majority of Blacks lived in the South and were tenant farmers renting acres from white landowners within a rigid racial caste system. The Hampton and Tuskegee models prepared craftsmen and women for a largely agricultural economy that was slowly shifting to an industrial one–the emphasis is on “slowly” between 1870-1930.

Subsequent reformers kept channeling minorities into vocational courses even after the Brown decision thereby continuing that school-based segregation (see here).

What Does Vocational Education Look Like in Classrooms?

Here are some classroom photos from early 20th century:

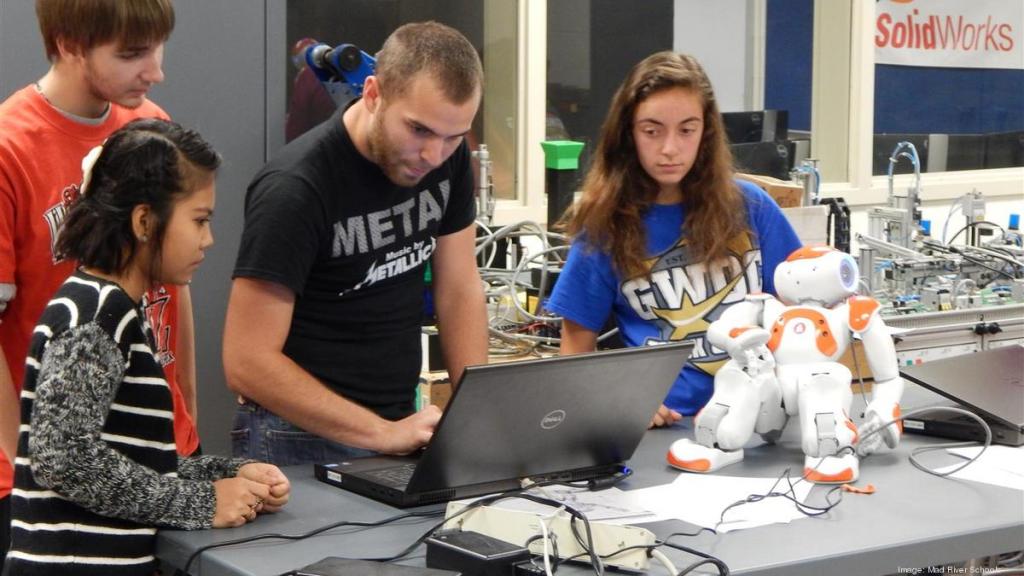

With policy criticism of vocational education as a dumping ground for minority students accelerating since the 1960s, especially after A Nation at RIsk report appeared in 1983, federal and state efforts to merge academic and vocational skills together in acquiring not just jobs but pursuing careers led to a re-casting of vocational education classes into Career and Technical Academies (see hereand here)

Did Vocational Education Work?

The effectiveness of vocational education since the mid-20th century has been contested by both policymakers and researchers.

One measure of effectiveness has been getting actual jobs in the specific fields that students prepared for (e.g., trade and industry such as auto repair, electrician, brick mason, . Another measure has been preparation for a suite of jobs in the vocation or career (e.g., business, health care, sales, information technology, human service occupations). A third has been to increase participation in vocational education and career and technical education. Researchers have reached negative, positive, and mixes of both conclusions (see here, here, and here).

At best, then, the research on effectiveness of vocational education remains contested.

What Happened to Vocational Education?

Since the early 1980s, it has had major surgery. Today it is called Career and Technical Education (see here). Major infusions of donor and federal funds has re-made CTE in a darling of policymakers, especially after the merger of academic and vocational experiences that opened up routes to higher education than had ever existed under the aegis of 20th century vocational education. With the policymaker mantra that everyone goes to college, CTE leaders march in cadence to that slogan.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.