David Labaree on Schooling, History, and Writing: School Gave Me the Creeps

This post is a piece I wrote not long ago, something I’ve been meaning to write for years. An alternative title is: “School — Can’t Live With It, Can’t Live Without It.”

See what you think.

SCHOOL GAVE ME THE CREEPS

Did you like school? I didn’t.

In way that’s strange, since I did well at school and in the long run it did well for me. It got me into college and graduate school and eventually provided the subject matter for my career as an education professor. Nonetheless, school gave me the creeps, and it still does. That’s one of the reasons I chose to study the history of education, so I wouldn’t have to step inside a school. The creepy feeling was especially strong at the elementary level. By high school it got better, as I was able to enjoy the camaraderie of a group of friends even while constantly worrying about being too nerdy and uncool. It was only in college I came into my own, for the first time able to embrace intellectual pursuits in a peer setting where that was not considered weird and stigmatizing.

But elementary school was fraught with chronic fear for me. Fear of being called on in class, humiliated in front of peers, dressed down by the teacher or conversely seen as the teacher’s pet, dreading bullies in the school yard, embarrassment around girls, and rejection by boys. I used to fake illness a lot in order to avoid going to school, which my mother tolerated on the understanding that I needed mental health days to recover from the daily ordeal of schooling.

I’m bringing this up because people like me – educators and educational researchers – need to remind themselves that school is not an unalloyed good. Too often, I think, we in the education business tend to lose track of the reality that schooling can be a very unpleasant experience for the students going through it. Often we had a good experience in school, finding ourselves in a positive environment where we thrived, so we decided to go into the education business instead of joining the real world. And often, like me, we did not have a good experience but managed to repress our early memories of schooling in the light of the later benefits it provided us – a good job and a respectable social status. Students who weren’t as shy and anxious as I way may not have had the same fears about school that I did. But then I was one of the lucky ones who did well at the tasks that schools value. What about the kids for whom school was a Sisyphean hell of recurring academic failure?

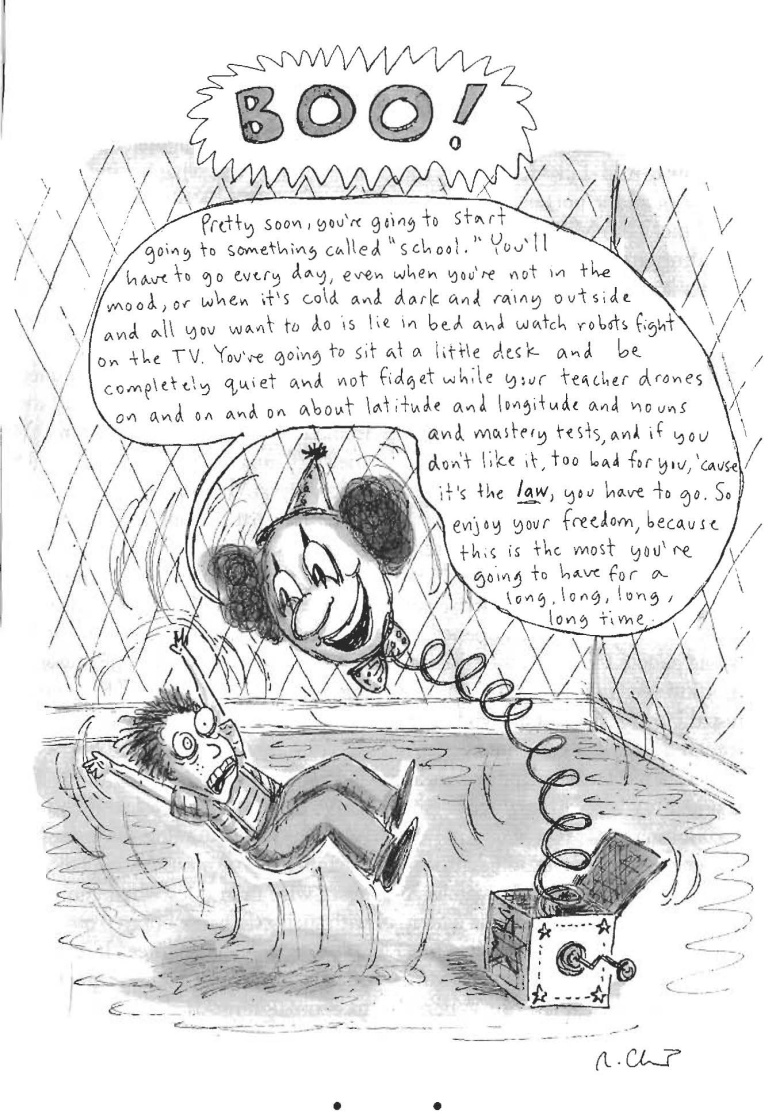

\We need to remember how unnatural schooling is, how foreign it is to the children who encounter it. Ripped from their families, kids find themselves thrown into the cauldron with hundreds of other students in a large building that simply screams “institution.” They are then grouped by age into classrooms of 25 or so. No longer unique members of a small family, they suddenly become part of a group of generic first graders placed under the authority of a strange adult. There they are subjected to a standard set of rules for behavior in a crowd, ordered by buzzers, and make to walk in quietly in lines when moving through the halls. And in between the buzzers they are harnessed to a standard curriculum that compels them to sit quietly in their seats for hours on end carrying out tasks they had no part in choosing.

As a child, you quickly discover that schooling is your job. You have to get up early every weekday morning for 180 days a year, march off to school with lunch and books in hand, and then march home at the end of the day, often bearing homework that you need to complete by the next morning. And this goes on for 12 years, 14 if you count preschool. Really, what an ordeal. Could anything be more unnatural and unpleasant?

Sadly the answer to this question is that for many children there are indeed worse ways to be spending their days. At least in school they have heat, hot meals, and a relatively safe environment, none of which may be true at home. Because of this factor, my timing in writing this piece may feel jarring, since so many students have suffered mentally from being barred from attending school in person. (I wrote two earlier pieces about what students lose when schools close.) This, however, this is less cause to praise school in my mind than cause to denounce an inadequate welfare system that denies many children the basics of food, shelter, and safety.

The batch processing of children in age-graded classrooms carries other costs as well. Pressed together with peers in the same room for a year, they find themselves in an intense social setting without the organizing principle of age that governs family life. You can’t compete with your older siblings, who enjoy natural advantages over you, but in a classroom of peers competition becomes the norm – a continual struggle over who is taller, faster, meaner, better looking, more assertive, more athletic, and – oh yes – smarter.

Educators focus their attention on the latter characteristic, which is facilitated by age-grading. Immediately upon entering school, students find themselves evaluated in hierarchical relation to their peers, using the abstract metric known as “grade level.” Are you above or below grade level? Smarter or dumber than your fellow classmates? Every question you answer, every homework you submit, every test you take locates you on a curve from high achiever to low achiever.

Meanwhile students develop their own hierarchies, largely independent of the teacher’s system of ranking. The teacher’s scale is based on individual merit as measured by the cognitive skills schools care about, but the students’ scale has a more Hobbesian quality about it. When the Leviathan is not looking, the students are busy working out a status order on their own terms. No student wants to look dumb to the teacher in academic terms but also no student wants to look inferior to peers in the terms that these peers care most about: popularity, personality, pulchritude, physical prowess, and power.

As a result, school can look like the worst of both worlds for students. They’re subject to the autocratic control of the teacher in the classroom matters and to the survival of the fittest on the playground. Take your pick – Alcatraz or Lord of the Flies.

For better and for worse, both of these characteristics of schooling are highly functional. The merit structure of the classroom inducts students into norms and skills they’re going to need in order to succeed in the public world of work in a modern society. Such societies are organized around individual attainment, where your social role and social status are established on the basis of personal achievement in a competitive setting – in contrast to the regime of birth status within the shelter of the family.

Schools are designed to lead students into this kind of public life and families are not. They teach independence (individualism and self reliance) while families put the priority on group membership. They teach achievement (with status based on what you do) while families teach ascription (with status based on who you are). They teach universalism (where general rules apply to everyone) while families teach particularism (where everyone is unique and subject to unique rules). And they prepare students for assuming specialized social roles in work and public life (where relations with others are narrowly defined and instrumental) while families prepare children for broad social roles such as parent and spouse and friend (seen as ends in themselves).

At the same time that all this socialization is going on in the classroom, another kind is happening in the schoolyard. There children are learning how to function with peers outside the supervision of adults. They will need these skills as grownups, when they will have to function without the guidance of direct external controls and to negotiate social order with peers in a variety of settings.

As students proceed through the grades in school, from elementary to middle to high school, they will gradually move from simple to more complex classroom settings (one teacher to multiple teachers), greater curricular variety and choice, and more autonomy. And simultaneously they will also be moving toward a greater reliance on peer groups and peer culture and more independence from school groupings and school culture. Over the years, grade by grade, schools are leading children toward adulthood.

Going through the process of schooling, therefore, is the critically important mechanism for turning children in a family into members of a modern society. So we can’t do without schools, but we still need to remember how painful this process can be for the object of the whole process, the poor beleaguered student.

School: can’t live with it, can’t do without it. We can value it without loving it.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.